Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” opens with the rising of a curtain. This is a tribute to classic theater — a rising curtain has been shorthand for “the show is about to begin” for centuries.

However, something is a little different here. These are not traditional theater curtains, but rather a window curtain; and yet, the message remains the same. Hitchcock is informing the audience, “The show is about to begin.”

This, of course, raises the question as to what kind of show would be watched through a window? The answer is, a voyeuristic one.

Voyeurism

Our hero/voyeur is none other than the legendary Jimmy Stewart, performing as a wheelchair-bound photographer spying on his neighbors.

But Hitchcock was playing a deeper game here. He knew who the real voyeurs were — the audience.

After all, it’s us not Jimmy Stewart eagerly awaiting the opening of those curtains.

Hitchcock understood this to be the unwritten agreement between filmmakers and the audience:

Storytellers for millennia have understood that there’s a bit of voyeurism in all of us.

Culturally speaking, “voyeurism” has a rather seedy reputation. But, now the voyeur was the hero. Ater all, it’s Jimmy Stewart and he’s going to prevent a murder — classic heroism, right? Is Hitchcock saying that, maybe it’s a good thing we too want to go to the movies, hide in the dark and be voyeuristic for a bit? Perhaps it’s a way of justifying our own desires if we can tell ourselves, “See, something good might come of my taking a peek?”

Cinema Evolved

Of course, film and video are no longer solely consumed in dark theaters. Video is now used everywhere from cinema to smartphones and beyond.

We still expect to be entertained via video — but we also expect to be informed, educated, spoken to, and heard from, all via the magic of the moving image.

The rising curtain is no longer the most common shorthand for, “The show’s about to begin.” Clicking “Play” ▶️ is a more common modern-day indicator for “showtime.”

And thus, the filmmaker-audience contract must evolve accordingly.

Technology has led modern consumers to expect their media to understand them.

- “The filter bubble” means that Google pushes me searches that are relevant to me based on what it has already learned about me.

- Gmail suggests ways to finish sentences based on my own common speech patterns.

- My news feed is biased towards my biases.

- Ads follow you across the internet based on your pre-existing signs of interest.

- And, likewise, we’ve increasingly come to expect messaging to be relevant to us as individuals.

Video, historically has fit Hitchcock’s model: for the anonymous masses hiding voyeuristically in the dark. And it has long been part of that “escapism” from our own lives that effective movies provide.

Personalized Video takes it from the masses and allows films to be made for an audience of one.

Personalized Video allows filmmakers and marketers alike to address their viewer by name, showing them their data and scenes tailored to the group and even to the individual.

But wait, the concerned viewer says, “If my video starts out addressing me by name — if my video knows who I am and has data — messaging tailored just for me — then I can no longer feel anonymous. I can no longer escape into the safe thrills and anonymity of cinematic voyeurism.”

It’s true — it is hard to hide anonymously when you are being called out by name.

So the question becomes, should we let the audience know we are tailoring the message uniquely to them? What level of personalization is effective but not “creepy?”

Data-driven video lets marketers, filmmakers, and basically anyone tailor the message to the individual, but should they?

And if we do tailor the message, should the audience be aware of it?

Or, should we tailor their messaging more subtly so they can maintain a sense of anonymity that keeps them feeling comfortable, safe, and nameless?

The answer largely depends on, “What are you already used to?”

Technophobia (fear of technology) is in fact rooted in neophobia (fear of what is new to a person).

The key is understanding your audience(s) and that that may require a solution that is not entirely, “one size fits all.” Which is why solutions that dynamically allow for different content for different users are so powerful. Users in such cases likely don’t even realize they are getting something tailored for “people like them.”

For example, younger audiences appear more comfortable with personalized and targeted messaging. Simply put, it’s not new to them — it’s the norm.

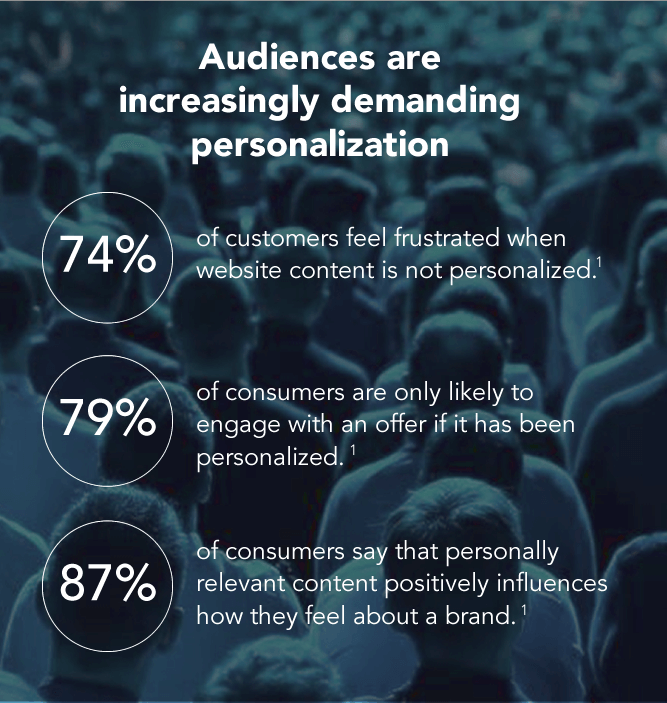

Personalized content in websites that made audiences uncomfortable even a decade ago is now often viewed as a necessity. Audiences are increasingly demanding personalization.

Mark Zuckerberg explained the logic behind Facebook’s news feed algorithm as, “A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.”

Audiences are indeed progressing from uncomfortable with personalization towards demanding it.

Just as cave drawings gave way to hieroglyphics and storytellers enjoyed millennia of oral traditions before the advent of the written word (and later, movies), so too, the moving-picture has come a long way since Hitchcock’s time. The screen has gone from the theater to, well, everywhere.

The question becomes: In the cinema of the future, will the audience want to watch a movie, or will they demand their movie.

As audiences come to demand more from their side of the agreement, it’s on filmmakers to evolve accordingly. It’s time for creative professionals to write a new “audience-filmmaker” contract.

Source:

1. https://instapage.com/blog/personalization-statistics